Excerpt from The History Of Granville: Licking County, Ohio (1889)

On our southern border, in the valley of Ramp Creek, near Cherry Valley, one evening in the late autumn of this year 1800, a settler from the valley below was threading his way through the forest, hunting for deer, when he came unexpectedly on a camp fire. Around it were gathered five men ; Benoni Benjamin and his three brothers-in-law, John Jones,' Phineas and Frederick Ford, and the fifth, a man in Mr. Jones's employ, by the name of Banner or Denner.

They were exploring with a view to settlement, having left their families back on the Scioto.

HENRY BUSHNELL

There’s a field near my home that I can almost see from our bedroom window.

It’s one I’ve driven past thousands of times, a nameless field that blends into the background of my daily routine. As a kid, my school bus drove by it twice every day. I rode my bike past it on my way downtown. As an adult, I have to drive by it every time I get on or off the highway.

Towards the end of every summer, my wife and I start going on “deer walks” to watch bachelor groups of bucks slip out of the timber in the evening light to graze the goldenrod.

For most of my life, it was just a field.

Until our village planning commission offered up an opportunity for the community to vote on it’s future, I never thought to look up who had walked it before me, or what it looked like before roads and subdivisions sliced it up.

I didn’t even know it had a name. Munson Springs.

Turns out, this field is not just a field.

What’s Buried Beneath

Licking County has to be pretty observant when it comes to development, and it’s not hard to see why.

You don’t have to dig far here before you hit something important.

The Newark Earthworks, built by the Hopewell culture more than 2,000 years ago, sit just a few miles away. They’re some of the most impressive and intact geometric earthworks in the world. Designed with astronomical precision and cultural significance we still don’t fully understand.

Other smaller mounds dot our local landscape, but many were destroyed by farming or development. When you grow up around these things, you start to get a little numb to the weight of their cultural importance.

Excerpt from The Frontiersman

[March 12, 1775 — Sunday]

“From this site they could see the spot near the edge of the canebrake where Simon [Kenton] had shot the doe. A buffalo trail so well trodden that it was a better road than Simon had seen in the east passed near their camp and they followed it into the interior. It led directly to a tremendous bubbling spring of the clearest blue water imaginable … The trees and fields were full of turkeys and squirrels, pigeons and quail and grouse. It was a land of dreams, a land that far surpassed even the extravagant tales Simon had heard about it. And because the game from miles around came here to lick salt at the springs which fed the large river, they named it the Licking River and the bubbling springs themselves were called the Blue Licks … There was much sign that the Indians came frequently to hunt, as evidenced by the trails obviously made by the moccasined feet of men…”

ALAN W. ECKERT

What Drew Them Here

In the late 1980s, the same field I’ve driven past for years was slated for a housing development.

Before construction started, a small excavation team went in to make sure there wasn’t anything important under the surface. Well… there was.

Buried in that field was a fluted point. A rare artifact from the Paleoindian era, dating back over 12,000 years. To find a fluted point in situ—undisturbed, exactly where it was placed—rarely happens. There are very few in situ Paleoindian points found in general. But this field held one.

It remained right here. Still in the ground, exactly where it had been left.

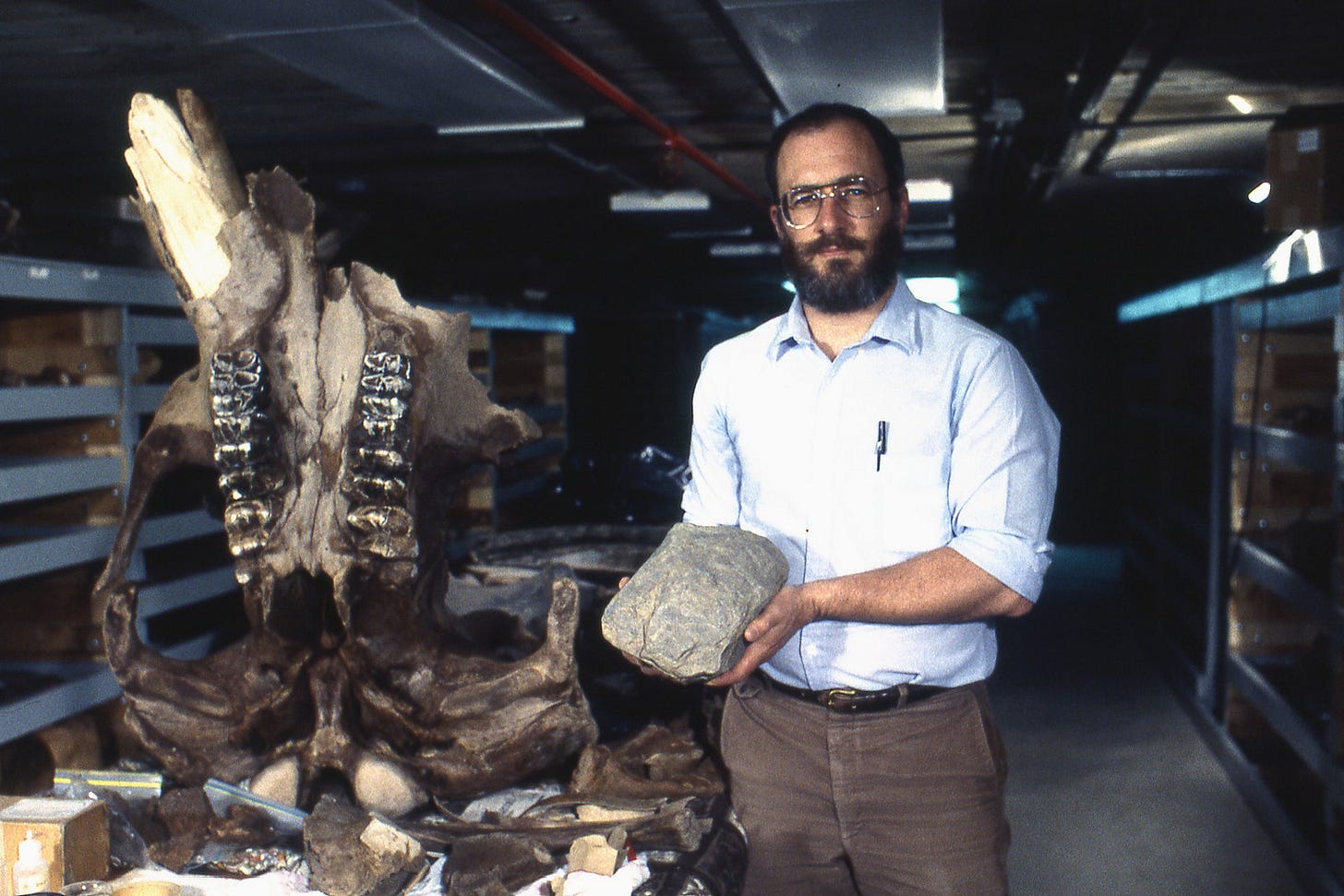

This whole region is full of signs like that. A few miles down the road in the same year, a pond was being dug on a golf course when they hit something. Bones. Big ones.

What they uncovered was the most complete American mastodon skeleton ever found. It became known as the Burning Tree Mastodon.

Still had food preserved in its stomach.

So what were they all doing here? The answer, like most things, is simple if you know what you’re looking for.

Salt.

The Licking River’s original Shawnee name—Nepenime Sepe—means Salt River. The mineral deposits brought in mastodons, elk, and deer. And where there’s game, there are hunters.

That’s the pattern. The salt brought the animals. The animals brought the people.

Even the road that borders this field—Newark-Granville Road—started as a trail. First used by animals, then turned into a buffalo trace. Then a wagon route. Now, blacktop.

We didn’t carve it out. We just followed what was already there.

It’s easy to think of the hunting tradition as something we preserve simply because it’s a part of American history. But this is older than that. Hunting predates colonization, settlement, even agriculture.

Hunting is history.

The Gateway to the Midwest

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, settlers were pushing into the Ohio River Valley, looking for land to claim as their own.

The natural springs provided fresh water, the forests provided timber and game, and the old hunting trails became well-worn paths for traders and settlers.

Jesse Munson, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, arrived in 1805. When he reached this field, he told his son to buy everything he could see.

So he did.

They built a house. The spring became Munson Springs. And in 1808, just a few steps from where that Paleoindian point had been left centuries earlier, the Licking County Common Pleas court held it’s very first session in a log cabin in the very same field.

What struck me wasn’t that history happened here. It’s that it happened in so many layers. All in the same spot.

The field didn’t have a beginning and it clearly doesn’t have an end.

It just keeps changing hands and adding chapters to the story.

What This Field Reminded Me

For a while now, I thought the heritage, tradition, and values of hunting and fishing as something that needed to be preserved. Something we were in constant danger of losing.

But this field tells a different story.

These activities aren’t something that gets erased overnight. It’s something woven into the very fabric of a place. It doesn’t just belong to one generation, one community, or one way of life.

It’s older than the county, older than the settlers, older than written history in this part of the world.

I see this field now as connection point. A common thread thousands of years old.

From the mastodons to the salt licks. From the buffalo trails to the settlers. From the fluted point to my evening deer walks.

We aren’t just carrying on a tradition. We’re walking the same ground, following the same trails, and if we try hard enough, we can still live in the same rhythm.

When I drive past this field now, I see more than just open space.

I see what has always been there.

From My Desk:

What I’m Thinking/ Doing: I thought we were entering Spring, but as often happens in March here in Ohio, it was just another fake spring. Seems as if warmer weather is on the horizon of the 14-day forecast, and with it I can almost hear the gobblers picking up steam over the next ridge.

On Deck for Monday: This past week was by far the busiest of 2025 to date. It feels good to actually start crossing things off the list and making noticeable progress. Looking to stack productive weeks back to back.

From The Field Review Archives:

The Field Review is a space for exploring the intersection of work, life, and the great outdoors. It’s about figuring ‘it’ out—whatever your ‘it’ might be.

Every Sunday at 10AM EST, I share ideas, insights, and conversations that help break through the noise, offering a real look at how we can all keep moving forward.

If you have any thoughts, questions, or topics you'd like me to explore in future newsletters, feel free to reach out!

Venture Onward,

Jack